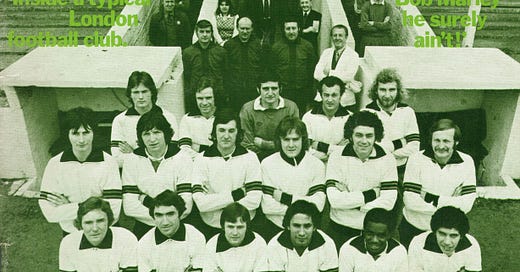

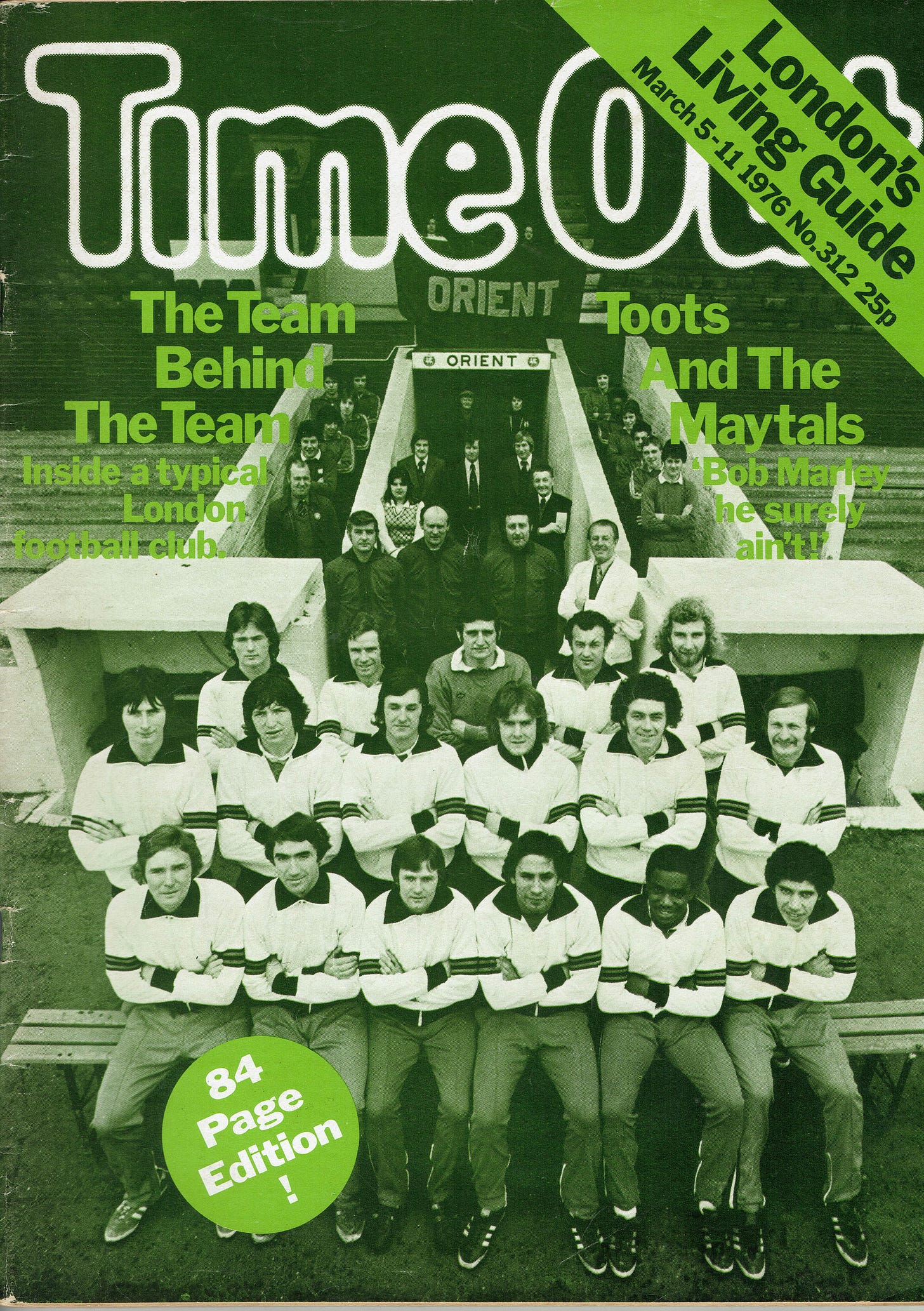

ORIENT EXPOSED!

The year is 1976, and Orient are sufficiently fashionable to merit a feature in Time Out magazine. What we'd do for this kind of coverage today...

'People think, 'said Orient's physiotherapist Ernie Shepherd, 'that a football club only exists on a Saturday afternoon. ' In fact this London second division side figures daily in the lives of a host of paid and voluntary workers. Peter Ball talked to the team behind the team.

'There's no "upstairs, downstairs" in this club,' said Brian Winston, Orient's young (37), energetic chairman. Oh well, I thought, there goes the idea that Orient are the archetypal football club— not too big, not too small, nestling safely in the middle of the second division. 'No,' he said- 'When we have parties we all are equal, none of this patronising attitude, the gin and tonics for us and beer for the lads routine.'

You didn't believe that that attitude still existed, did you? It does. In fact not so long ago I heard an ex Chelsea star—a star earning £10,000 to £12,000 a year with his current club—address Chelsea chairman Brian Mears as 'Mr Brian'. Really. Not even Mr Mears but Mr Brian, with all its flavour of nineteenth century family retainerism, that blend of familiarity and servitude. Well maybe that's unusual too; except that at Charlton the chairman is Mr Michael (to groundstaff lads and the manager too), and at Ipswich—Mr John. But at Orient, chairman Winston is just called 'Brian'.

So Orient isn't typical—in terms of attitudes anyway. Everyone there says it is a friendly club, and a young club. The sort of club where a supporter will turn up with three bottles of sherry for the players after an away defeat, because they played so well. That's what football clubs can be about.

But are they really clubs? They are, after all, limited companies. And structured like businesses, rather than like clubs. To draw an analogy with cricket: one of Surrey's first moves to improve their financial position last year was a major membership drive in the whole county. Orient, in a similar position, are issuing shares: 320,000 at 25p each. This will increase the company's capital from its current £20,000 (80,000 shares) to £100,000. And unlike other clubs, Villa for example, the new shareholders will have the same voting rights as owners of the original shares.

If the new share issue follows the old, Orient will be a much more open club than most. Of the 50,000 shares currently not held by the directors, no more than a few hundred are held by any single individual. And the vast majority of the 900 holders own only 20 shares or less. You could call it another form of club membership, except that attending the AGM and expressing an opinion apart, there are no benefits to membership. And because of FA rules, there is one major difference between football clubs and other limited companies.

Shareholders are restricted to a minimal dividend, 10%, which is rarely paid anyway. If Orient have ever paid a dividend, which secretary Peter Barnes doubts, it was in the dim and distant past. And directors are barred from receiving any payment for their services. Which means that a football club has no senior executive in the form of a managing director.

In Orient's case the chairman fills a large part of that role. But he has to do it in the time he can spare from his own profession. In business terms it hardly makes sense. As Brian Winston says: 'The ban on paid high level executives is absurd. It means that successful businessmen, people who have made a success of running business, can't run soccer effectively. If I could be at Orient as a full-time managing director, I'm sure I could run the club profitably.' As it is there isn't time.

It also means that very few of the elder statesmen from inside the game become directors. At Orient Arthur Rowe—manager of the early fifties Spurs side and one of the game's greats— acts as father figure and confessor for the club, as well as filling his official function of chief scout and youth team adviser. But although his salary is fairly nominal, the acceptance of a salary bars him from a directorship—where one would have thought his experience would be invaluable. Again unlike cricket, where county committees are littered with the names of ex-players.

Football loses at both ends. The successful businessmen who become directors are prevented from using their business skills in the day to day running of the game. On the other hand, because the FA Council has Oxbridge representatives alongside all the County FA reps on it, an Oxford University spectroscopy expert, Sir Harold Thompson, who once ran a successful amateur side in the fifties, has more say than the professionals in selecting the England manager. And a major FA Committee, at a time when the financial clouds are gathering ominously, can devote itself to making policy statements about players kissing on the field.

By those standards, and possibly by much harsher ones, Orient are a remarkably well run club.

The Directors

Football club directors come in all shapes and sizes. It’s generally thought that you have to have a lot of money to be a director. But that isn’t a universally common denominator. Nor is a total lack of football knowledge, in spite of everything players will tell you to the contrary. According to Brian Winston, ‘directors are fans’. Undoubtedly true in his case. He stood on the Orient terraces as a kid, and has been known to stand with the supporters at away matches. But, as he admits, in some clubs directors are there because they want the status and the prestige, not because of life-long supports for the particular club. Often the local rivals, Ellis of Villa had been on the Birmingham City board. Mortimer of Luton was previously a director at Watford. And the Portsmouth chairman had joined the club when he failed to get accepted by Southampton fans?

The other directors at Orient really could be called fans. Harry Zussman, an East End businessman described by Winston as a ‘cigar-smoking football ambassador’, has been a director for nearly 30 years, including a long spell in the fifties and sixties as chairman. FF Harris, a publican, has been a director for 20 years. Max Page, the son of former chairman Arthur Page, joined the board at the same time as Winston in ’73. All have longstanding ties with Orient. Something many club directors couldn’t claim.

Money, as we said, is not a necessity. If you want to be chairman and call the shots then obviously some is essential. But even at that level the Ray Bloye, John Deacon (at Portsmouth), Bob Lord type are an exception. It needn’t even cost very much to buy your way in. At Orient, where the current share issue is 80,000 at 25p each, the directors own around 30,000 between them. At the last published accounts, Winston had 9,384, Zussman 11,958, Harris 4,400 and Page 3,000. If you estimate that Winston paid 30p a share (and it is doubtful if it was any more), that’s just under £3,000. Quite cheap, really, for the prestige, power and fun.

Ah but what about directors who are dipping their hands into their pockets the whole time to keep the club going, paying the player’s wages, all that sort of thing? And guaranteeing vast overdrafts at the bank? Winston dismissed that scornfully. As he says, he couldn’t afford it, not can most directors. It happens at a few places. But even at clubs where they count their overdrafts in six or seven figures, directors often don’t stand as the main guarantors.

Directors’ guarantees did cover some of Orient’s £33,400 overdraft in the 73-74 season. But most of their security came from two houses which the club happens to own, though they don’t own their own ground. (Reflecting on clubs who’ve got heavily in debt borrowing against their ground, Winston thinks not owning theirs is O’s greatest asset).

In Winston’s case, he estimate that his chair costs him about £1,000 a year, and one of the other directors probably spends the same. Money spent on paying their own fares to away games, paying for players’ dinners on trips, buying drinks etc. It’s what others might spend gambling, or heavy drinking, a meal out twice a week, or golf.

A Working Chairman

In a football club directors’ duties are often unspecified. Apart from the statutory Board meetings, they may only be seen at games. And at some clubs even the Board meetings are few and far between. Notts County, at least in Jimmy Sirrel’s day, were famous for meeting once a year to pass a vote of confidence in the manager. At Orient they meet regularly. But Brian Winston is the director the staff come into contact with most frequently, reckoning to spend about a day a week on Orient business. In effect an unpaid, part-time, managing director.

Everyone at Orient was full of praise for Winston as chairman. All defined him as a 'working chairman', someone who was quite happy to help licking stamps when they had a lot of tickets to send out. What though Is a working chairman? What does he do?

Winston defines it as 'being amongst the people who do the work'. He trains with the players on occasion, and tries to get close to them. Successfully enough for manager George Petchey to ask him to motivate a player he's failing to get through to. On matchdays Winston says he endeavours to get round all the areas—players, programme sellers, police, the ticket office—making sure there are no problems and generally trying to act as a morale booster. Plus of course spending a day a week at the ground covering administration and helping with business problems. And regular daily contact with Petchey. But although his day to day involvement is probably greater than most, in the end day to day organisation comes down to the secretary and manager.

The Secretary

The secretary of a football club is almost the general dogsbody. The range of duties, particularly at a small club, is quite amazing. If you phone Orient, it's quite likely that either club secretary Peter Barnes, or his assistant, Mike Blake, will answer the telephone. They and one other assistant are Orient's weekday office staff. A big club, like Arsenal, has a typing pool, a wages clerk, a ticket office etc etc. An ordinary member of the public would need a pretty good reason to reach the Arsenal secretary, Ken Friar. At Orient, the staff of three cover the lot from ticket sales through fixing up travel and hotels for the team to balancing the books, paying the bills and, occasionally, dealing with shares as any ordinary company secretary. Plus overseeing work on the ground and behind the scenes, and organising the parttime stewards and gate-keepers. It's not unknown for them to sleep in the office. Mike Blake writes and produces the programme in his spare time. It is, unquestionably, a labour of love. As George Petchey says, 'They do five people's work, and get not very much money.'

The Manager

The other chief executive is-of course the manager. Ah well, we all know what he does, don't we? He looks after the team. Well yes. But even there there are some wide divergencies. Both in the amount of staff to help, and in the extent of area covered. At Orient George Petchey works as a track suited manager —a coach in all but name. Except that he negotiates the players' contracts, and has considerable responsibility for financial arrangements. As he says 'Getting money in is my job. The biggest pressure is to get enough money to keep the club going.'

Petchey estimates that administration occupies two days of his week. He has to liaise with Peter and Mike about weekly wages, the team's travel plans and suchlike. Dealing with the press can take. two hours a day. Administration is spread over afternoons and evenings— he takes work home because his wife and daughter are good typists! Mornings, of course, are spent with the team. And through the year he reckons to see two or three games a week. The only time off is Sundays, and the occasional day midweek. Long hours and a lot of responsibility. Results? Balanced books and good public relations. (He's been known to spend hours discussing the team with fans who drop in to voice their opinions.)

On the playing side, Petchey has three full-time assistants. But he does much of the day-to-day coaching of the first team himself. In the end a manager stands and falls with the team and its results. Even at Orient, where Petchey has an understanding chairman with faith in him and the club's setup, he knows that 'football is a business where the demand is for instant success. And the instant remedy for failure.

Our future is good, because we have got good young players. With reasonable results I'll be OK, but if we slipped down the League, and relegation looked possible, it is on the cards I'd get sacked.' That's the fate of every coach or manager in the game. It doesn't matter what you call them.

But Petchey’s job is wider than most. Consider his financial responsibilities: 'We have to get £45,000 a year to keep the club going. And it can only be done by selling players’. At the end of last season Petchey sold three players for £20,000. And the decision was taken to hold the weekly wage bill to £2,000. This was accomplished partly by relying on the Orient youth policy (approximately two-thirds of their 24 professionals are 20 or under) and partly by releasing 13 players during the previous year.

In a way it’s a thankless task. As coach, Petchey’s job is to build a successful team. But the books demand that Orient sell players to live. It's a question of 'getting young players and grooming them to sell'. Something which, one would think, inhibits building a team. 'It's up to us to produce the quantity to sell and keep us in the top 40 clubs.'

As manager of Orient George Petchey has his own team: the players, and the people who service them directly— coaches Terry Long and Peter Angell, and Ernie Shepherd, the team physiotherapist. This season, when Orient have been bedevilled with injuries right the way through, Ernie's job has been an exceptional one. His treatment room, a remarkably well equipped cross between a surgery and a hospital operating theatre, is almost as busy as the offices. And a lot busier than the sauna off the home dressing room.

The Off-Field Team

But there's the other team—the carpenter who has to mend seats every week, the two women who work every day in the club laundry room. Not something you think of immediately about football clubs, but essential. In fact Mike Blake describes washing machine breakdowns as 'almost our major problem—together with stand seats'. The carpenter is one of Orient's full-time staff, his main job being to mend seats broken by people climbing over them and turnstile doors, which also receive heavy treatment. The launderesses work five half days a week, plus all day Sunday, washing the kit from games and training.

Then there's the groundstaff: a fulltime groundsman, a maintenance man, and five or six part-time helpers, who look after both the ground and the training ground. At a big club like Arsenal, carpenters, electricians and groundstaff add up to 20 full-timers. And all the work is done from within, from the installation of floodlights to the wood panelling in the secretary's office. Orient haven't got that sort of staff. It's one man and voluntary help. Including supporters painting the stand a couple of years ago. Then there's the commercial office, a major factor in any football club these days. Manchester United employ, according to Mike Blake, 40 people in their pools office alone. That's almost the total Orient staff.

Orient's commercial manager, Brian Blower, has one part-time and two fulltime assistants. The part-timer, Tim, who can remember when the Prince of Wales went to see Clapton Orient, in 1920 was it? That's what behind the scenes at Orient is about. That and the woman in the commercial office who works full time driving round the country distributing pools tickets to supporters in places like Ramsgate, Aylesbury and Norwich. Although she covers over 1 ,000 miles a week, this delivery is still cheaper than using the post.

In the end Orient get by because their off field team is willing to sweat their guts out over very long hours for very little money. They are a nice, friendly club, and could still finish as the top London second division team. Yet Orient are still having money problems. Which tells you a lot about football's finances.

Business

Orient need an average gate of 8,500 to break even. At the moment, they're only averaging about 6,000. Which gives them receipts of around £3,150 from a home game. Half of that goes in match expenses, the Football League levy, VAT, the opposition's percentage; leaving Orient about £1,500.

That's the basics. With one major point to be made. It occurs roughly once every two weeks. And Orient's weekly wage bill is £2,000. So there's a £500 deficit on the home game week alone. Earlier in the season Orient suffered the horrors of not having a home game for three weeks. Thanks to the Football League computer, which apparently cannot cope with the old practice of a home-away-home-away routine. It meant virtually no money coming in for three weeks. As Mike Blake said, 'a disaster'.

Away games vary. Orient travel everywhere by coach, which obviously saves money on rail fares. That example, something third and fourth division sides have long lived with, is now being followed higher up. Earlier this season Manchester City were at Norwich for an evening game. They not only travelled by coach, but returned to Manchester after the game rather than spending the night in Norwich. Orient do stay at hotels when necessary. Although they get cheap rates from a hotel chain (around £4.50 a head), meals, which footballers eat out of normal restaurant hours, are a major expense. An average away trip ends up at about £250. (When Arsenal went to Newcastle, first class travel and hotel costs ran their bill up to £1,200).

At away games the club gets 13p a head for every adult spectator and 7p for every kid. So on a gate of 5,000 a visiting Orient collect about £600. At Sunderland, with a 28,000 gate, they received But that, and the £4,000 from a League Cup trip to Birmingham, are exceptional. Their average away league gate this season has been 11,000. Producing about £1,200 less £250 travel costs, or around £950.

While the team is away, there is, of course, the home reserve game. The average gate of 400 just about covers the match day expenses. Orient reserves are also in the London Midweek League and have now started to play these in the evenings—the greater gate covering the floodlight cost of £30 to a match. But financially these games pull little more than their expenses.

Adding it all up, on the football side, over a normal fortnight of one home and one away match, Orient bank around £2,500. That's on average. There may be the odd bonanza like the Birmingham trip. Which is the hope of every small club. And which leads Brian Winston to declare Southport, apparently the club with the most desperate problems in the League, a lot better off then Chelsea, Palace or Stoke. 'One trip to Liverpool for a cup tie, and Southport will have their problems solved for at least a year.'

But for Orient that hasn't happened this season. The League Cup was useful, but it was only one game. The FA Cup, the major money spinner for a small club, produced a home draw with a third division team on a day when West Ham and Spurs were also at home. In spite of that Orient pulled in 8,000. But they lost. Therefore no hopes of a trip to Old Trafford, Anfield or Arsenal this season.

It All Costs Money

In the summer a football club has no match income, only its season ticket sales (Orient's bring around £22,000) but wages still have to be paid. Then there's everyday running expenses, and not such everyday expenses. Rent, rates, lighting, heating etc. Two years ago Orient's rent and rates were £4,500; lighting, heating and water cost an additional £2,500. Even with economies, those have increased fairly dramatically. Orient have three pitches, two at their training ground and supporters club social centre in Spring Hill, Clapton. Maintaining them is a major expense. Two years ago it cost, including repairs and renewals, £3,700. Now? Metal goalposts cost £250 a set; nets over £100. A lorry load of soil is around £100. Mower maintenance, fertiliser etc all add up.

Then there's kit. Boots alone cost about £16 a pair; each player probably gets through two pairs a season. The first team get a new set of shirts and shorts every year. The older sets are passed down to the reserves, then to the juniors, then used for training until they have to be thrown away. Socks get ripped to pieces on studs—another black mark against the cloggers. A new match ball, which has to be provided for every first team game, costs £18. To save that expense Orient have ball donors—supporters or local businesses who buy the ball for a match.

Wages bills, as indicated previously, are trimmed by using a host of volunteers. 'This club,' George Petchey says, 'couldn't exist without voluntary labour.' That extends to everyone from the scouts who send boys to Orient to Petchey's wife's free typing to the four pensioners who help the maintenance man.

But if match day expenses don't reveal the whole story, nor of course does match day income. Commercial manager Brian Blower runs Orient's pools, the club shop, the Sportsman's Club at Spring Hill, and supporters coaches to away games. The former facilities make only small profits, but last year the pools brought the club £18,000.

And there are other sources of revenue. Two years ago advertisements in the grounds brought Orient £8,500. Then there's the club's share of TV fees, the FA Cup levy etc. They receive rents and fees for passing out their catering concessions, including a percentage of the take. But in the end it all comes down to match days. Orient are running at a loss unless they get that 8,500 crowd. At present they're averaging losses of about £700 a week. When the home gate drops to 4,000, as it did recently against Hull, a lot more.

And that's sad. Because Orient, and clubs like them, are what football in England is about. Not just the players, the up front people everyone sees (although the game would be much poorer without teams like Orient) but the behind the scenes workers who put in long hours for an ideal or paint stands in their spare time because it's their side. Football clubs are often the only focal point for a community. And with all their faults, those focal points are worth preserving. Orient certainly are.